Perez Art Museum Miami

July 18 - October 21, 2008

Sean: Duffy: New Work

Museum Essay

Peter Boswell, Assistant Director for Programs/Senior Curator

From the perspective of the 21st century, the 1960s in Southern California conjures up images of a lost golden age. Of the Beach Boys, car and surf culture, gasoline in the low $0.30s, The Graduate, and California Dreamin’. A time of sunshine, youth, few cares, and The Endless Summer. This is the era evoked by Sean Duffy’s new installation at MAM, with its zebra-striped Toyota Land Cruiser, its logo-bedecked tarpaulins, and its “Jerry” cans emanating pop music hits of the period.

The concept of a lost Golden Age goes back to the beginnings of time. For the ancient Greeks, it is mentioned by Hesiod in the 8th century BC as a bygone time when the earth bore fruit in abundance and labor was unnecessary, when there was no sorrow or grief, when age did not matter and death came in the form of peaceful sleep. In Judeo-Christian tradition, it is found in Eden before the Fall, when Adam and Eve were innocent and lorded over an earth made to suit their needs.

In our memories, each one of us has a Golden Age that we think back to as a time of ease and goodness. For some it is childhood, for others college days, for others still the first years of individual independence. In these personal golden ages—as in the cultural ones—memory sifts out the difficulties that troubled us at the time and leaves us only with the reminiscences we wish to keep. Thinking back to Los Angeles in the ‘60s, the Watts riots disappear, as does the Vietnam War, the farm workers’ struggles, the hangovers, the bad trips, and the individual anxieties caused by peer pressure, acne, early love, and all the rest. Our selective memory skims off the dross and retains only the gold, leaving us with a sanitized simulacrum of what was.

In art, repetition and reproduction have a similar distancing effect. With each remove from the original, the result becomes more homogenized, smoother, more stylized, more detached, less meaningful and less impactful, than what came before. It happens when music when a live performance is recorded, then re-issued in a new form, from record, to tape, to digital sound. Or when an original hit enters the popular mainstream and is “covered” by subsequent bands or ensembles, each of which render the piece increasingly generic. As changes in technology occur with ever increasing speed, the original becomes the copy that much faster, and our world becomes “virtual” that much quicker.

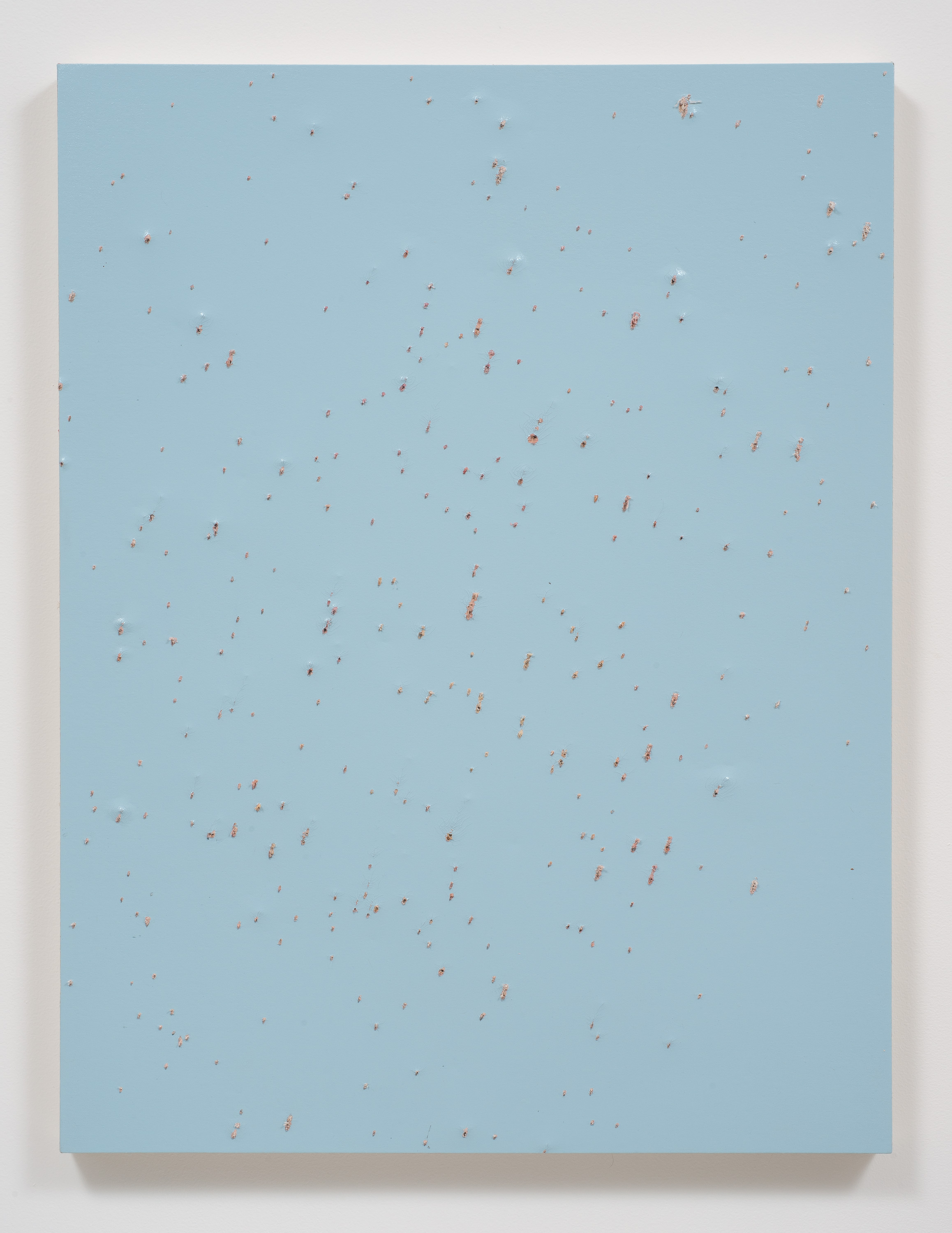

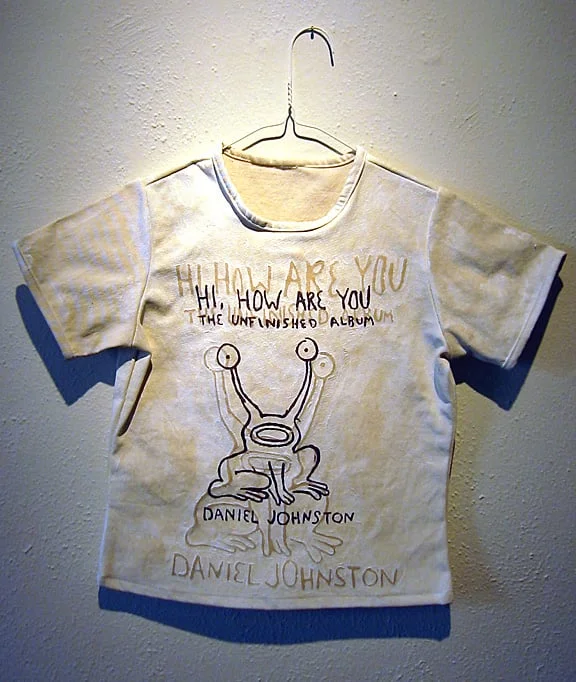

Sean Duffy has made this detachment, this step-by-step journey away from authenticity, a prime subject of his work for several years. But what could have been a nostalgic yearning for a lost—in reality, imagined—Golden Age, is in Duffy’s hands a mediation on estrangement and disengagement coupled with a doggedly-pursued search for authenticity.

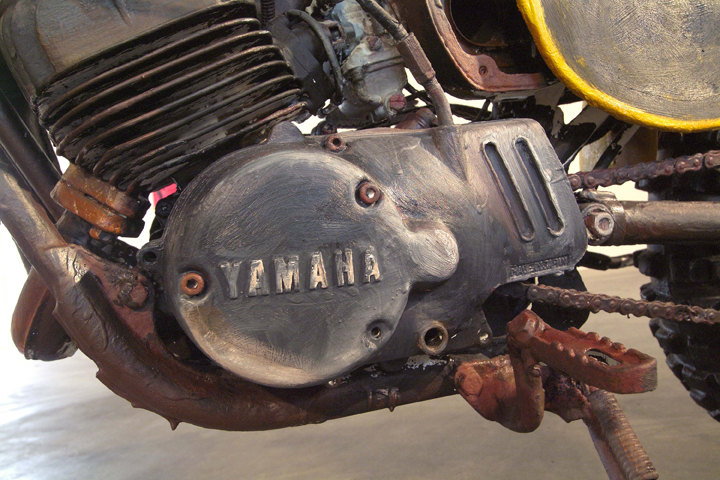

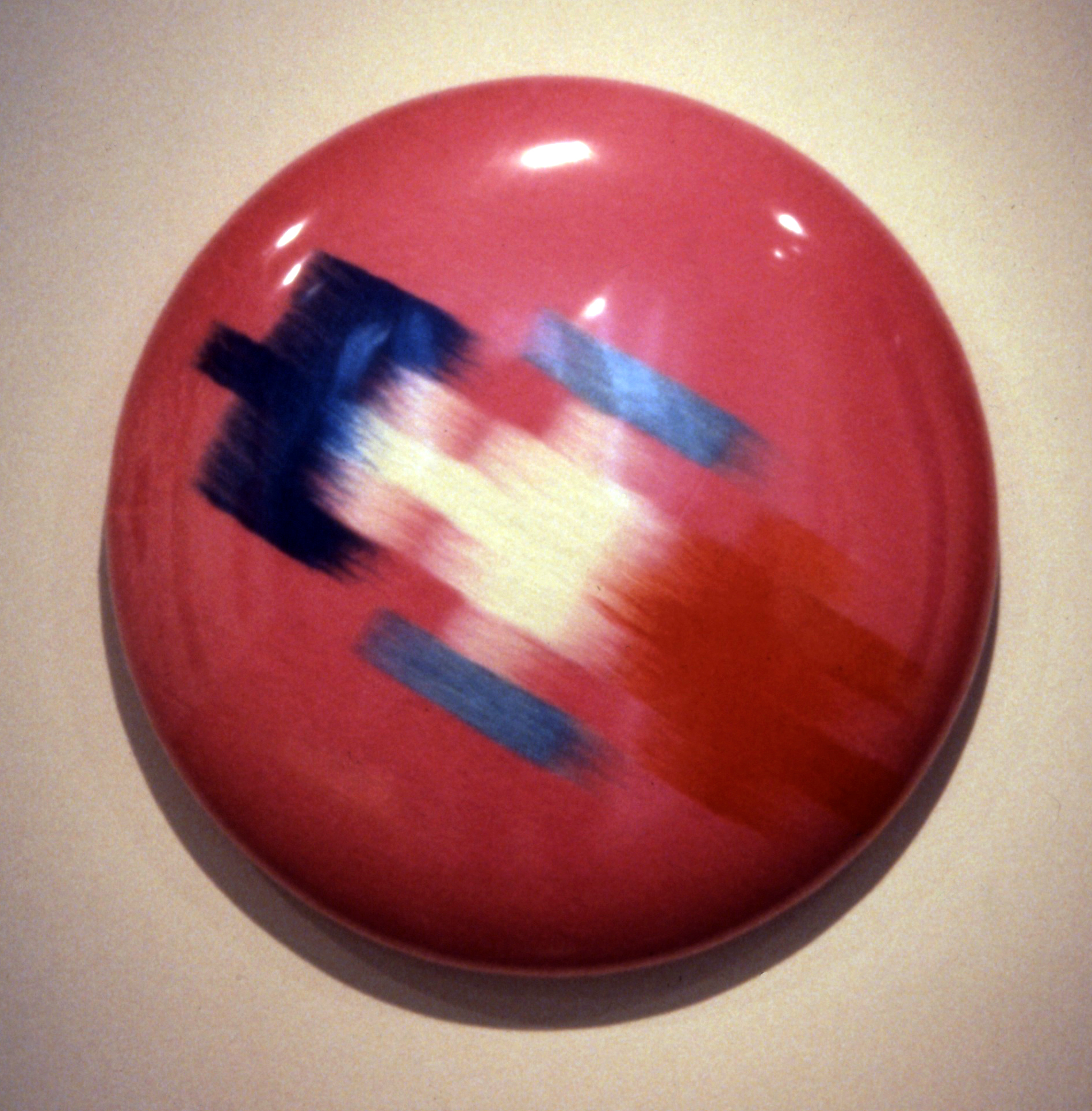

In 2006, Duffy’s first solo show, at Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, was titled Group Show. It included several pieces that reflected in different ways the complex interplay between copy and originality. The first piece the viewer encountered upon entering the gallery was 3rd Motorcycle, an apparent replica of Duffy’s own 1974 Yamaha YZ80, its every surface hand painted to resemble the absent original. But in truth, beneath the layers of paint, was not a replica, but the original motorcycle. Duffy had gone over every surface, from the torn leather seat to the mud-spattered tires, and painted the original to look as much like itself as he could. “The sculpture is an object that is a canvas for a painted illusion of the object—three motorcycles in one, all of them slipping into an untouchable image-world,” wrote Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Knight.[1] Nearby on the floor of the gallery was the similarly repainted First Helmet. One reviewer labeled these as “calculatedly futile attempts at the reanimation of aged objects,” the results of “a nostalgic impulse to resuscitate beloved objects from memory and discover the authentic through a process of duplication.”[2] By lovingly duplicating every detail of the objects, Duffy sought to rescue them from memory “get to know” them all over again. But for the viewer, of course, the original is lost beneath a layer of painted reproduction. Through his attempt to “reanimate” the object, the artist has, in fact, removed it from our reality and left us with a copy.

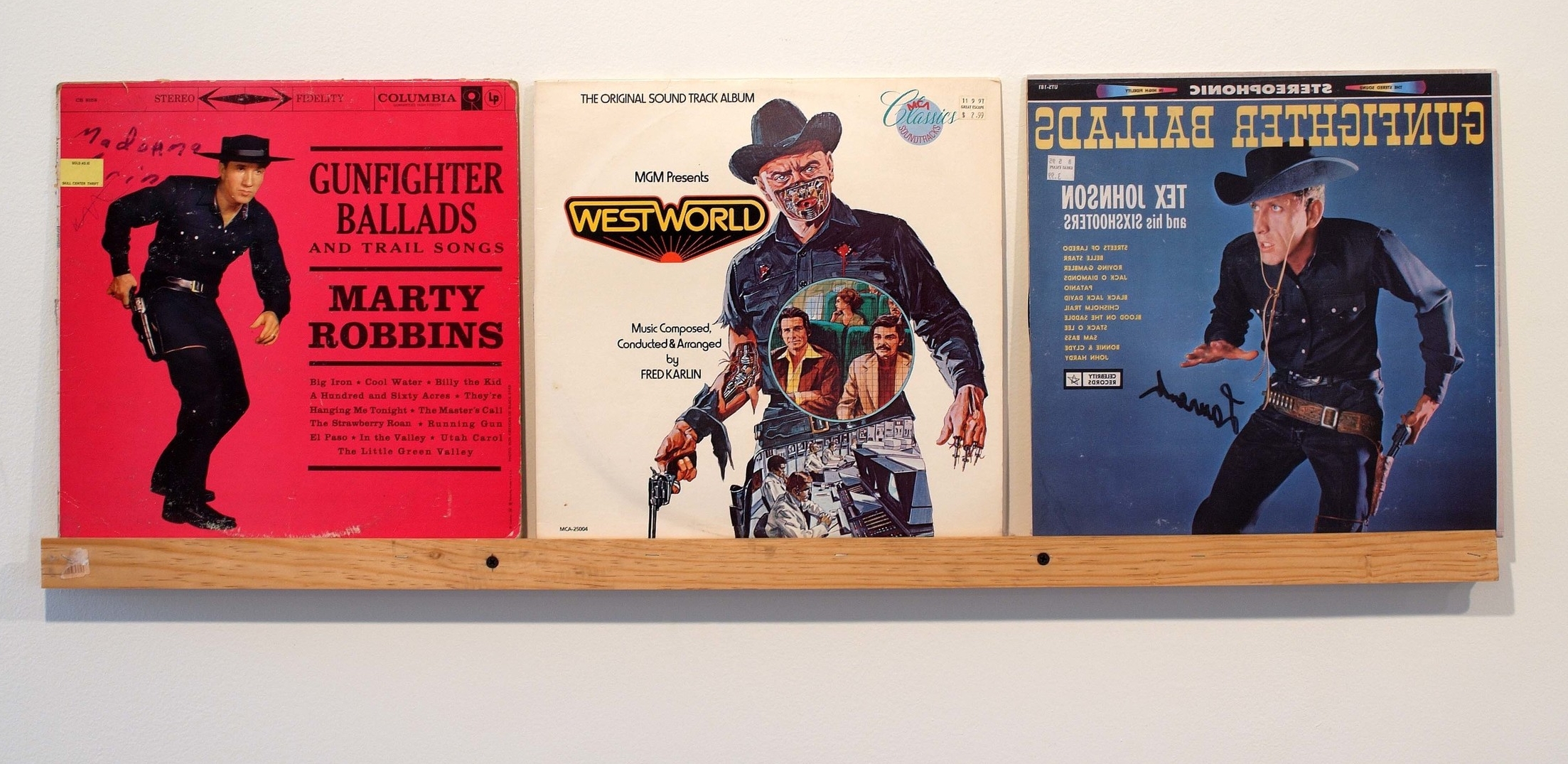

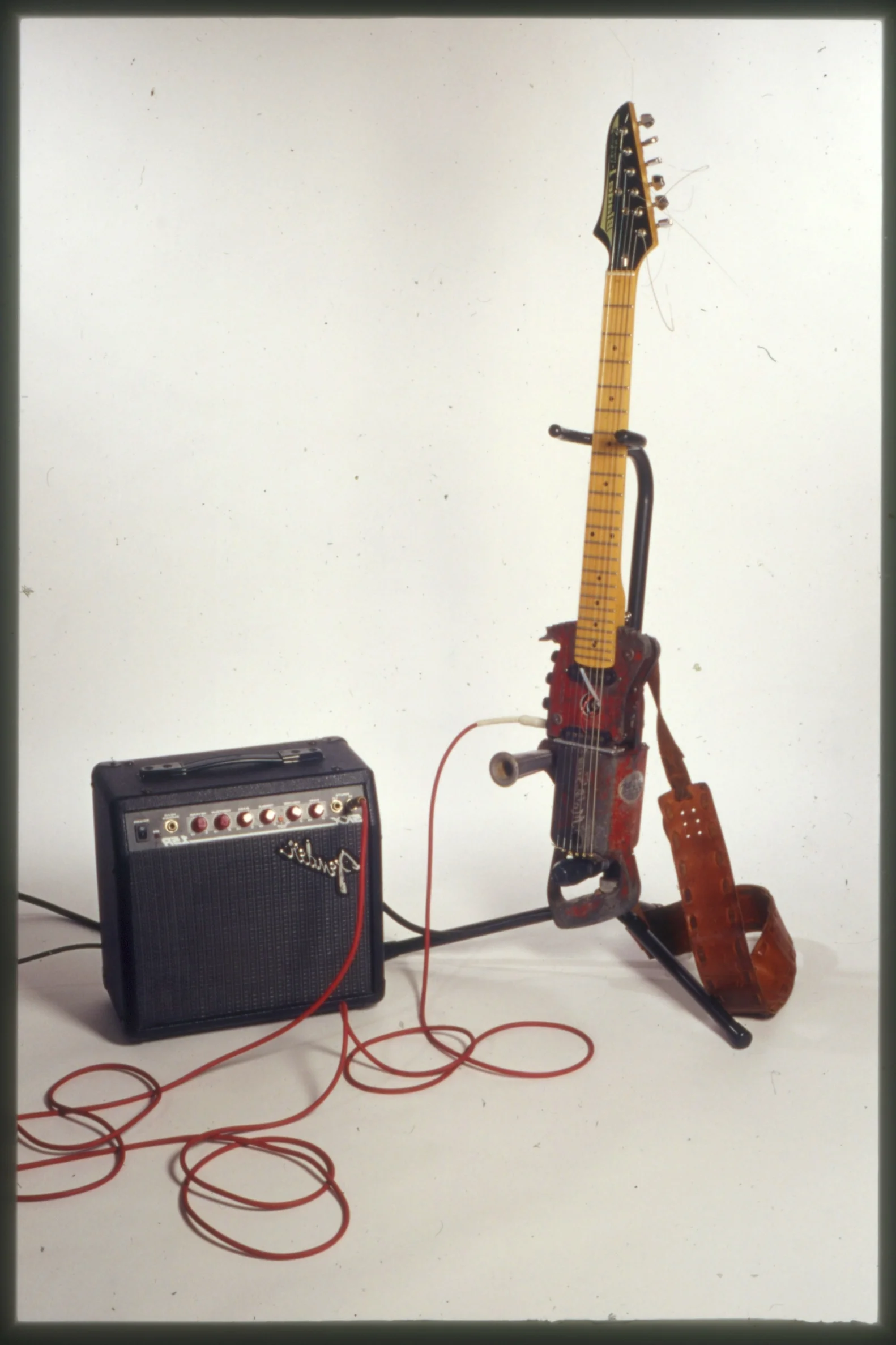

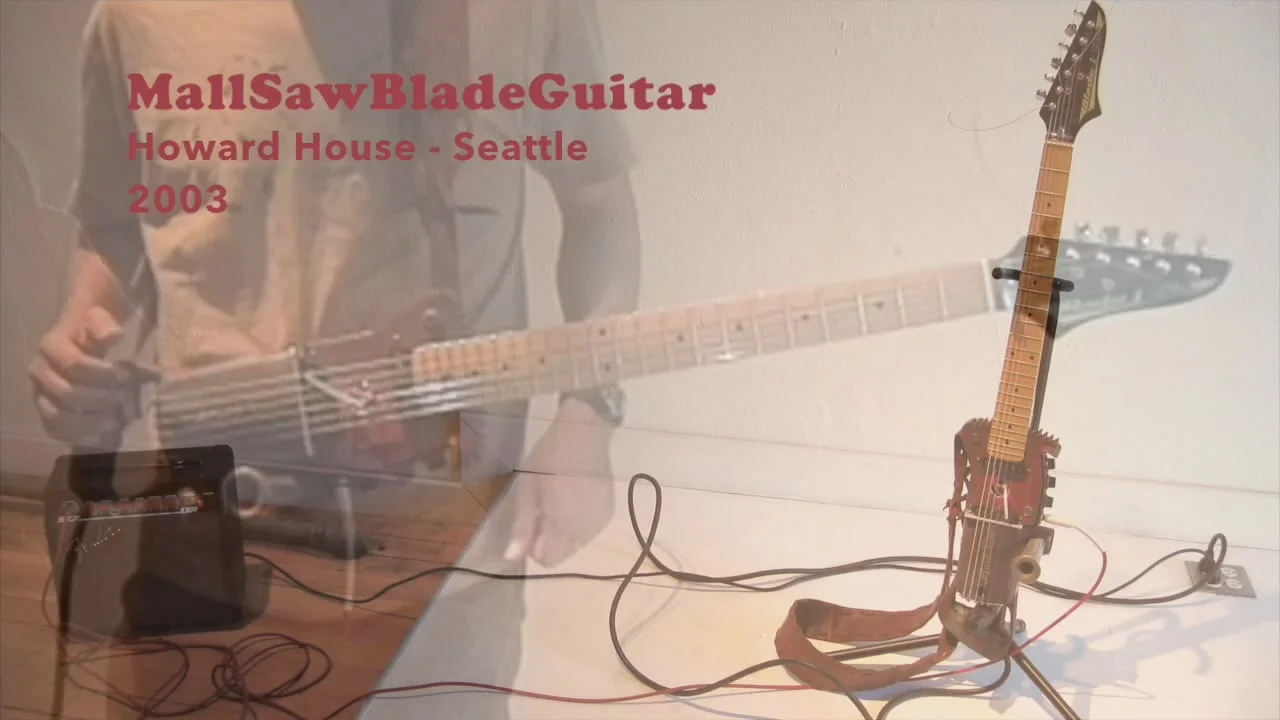

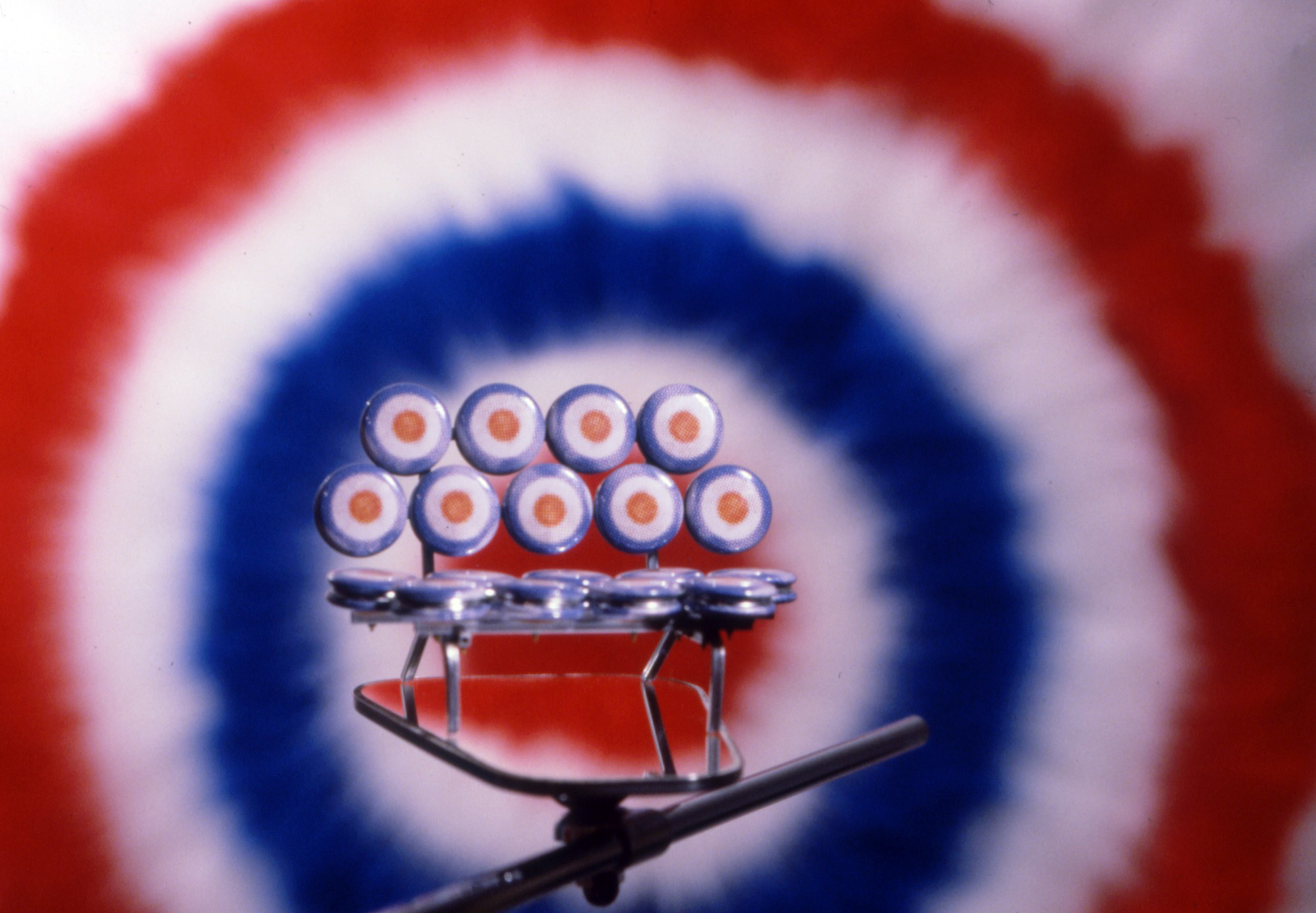

A different approach to wresting authenticity from mediated experience was found in another piece in the exhibition. The Good the Bad and the Ugly featured one of the hybrid turntables for which Duffy has become best known. This consists of three conventional turntable units fused together so that there is one rotating turntable, but three tone arms. When turned on, each tone arm plays the same record, but at slightly different times, resulting in a rondo-like sound effect. Duffy’s turntables are, in essence, a technology from the past (clung to by DJs and music aficionados who prefer vinyl records’ sound quality to that found in digital recordings) and his music choices—salvaged at bargain basement prices from used record stores—are intentionally dated. In the case of The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly, the record was the soundtrack of the 1966 movie of the same title, composer Ennio Marricone’s haunting melody eerily altered by its overlapping repetitions. Duffy’s choice of music was deliberate. The film that the music came from was a mythical evocation of the 19th century American West directed by an Italian (Sergio Leone), filmed in Spain, with an international cast of actors speaking in their native languages and then dubbed, and as interpreted through the influence of 20th century Hollywood films. Through his own intervention into the soundtrack, Duffy accentuates the hybridized, distanced nature of the film and our own distance from the historical reality of the film’s setting. “The elusive strategy Duffy performs is an act different from direct appropriation,” wrote Chris Balaschak, in a review of the exhibition in Frieze magazine, “He works not with duplication but with triplification, seeking a situation one or more steps removed from imitation’s mere copy.”[3]

In a crucial twist, two of the three turntable units used to create Duffy’s hybrid turntable were manufactured, but the third was fabricated from wood by the artist. “I tend to do almost all the work for any given show and have only used fabricators a couple of times… I feel it’s very important for me conceptually to physically work on the projects.” By hand copying the third turntable, Duffy became intimately familiar with the mechanics of turntables, thereby injecting a sense of the authentic (the handmade) into this instrument designed to emphasize detachment, or removal, from authenticity.

Duffy took the concept of alienation one step further in his Hey Jude from 2007, two flat screen televisions placed side by side, each showing half a turntable, including the tone arm. As the video plays on each screen, a hand places the tone arm on the record, whose soundtrack then plays on the audio system. As in the fused turntables, the images on the screens play at slightly different moments (the hand places the needle on the record slightly later on one than on the other), creating Duffy’s disorienting, rondo-like composition. By creating an image of a hybrid turntable, rather than a physical hybrid turntable, Duffy introduces one more step of removal. Significantly, the soundtracks Duffy selected for Video Turntable are “covers,” renditions of songs that are not by the artists who made them famous; versions intended to make the originals less original, more mainstream, more easily assimilable by consumer culture. By so doing, Duffy underscores how, as an element becomes more and more a part of our culture, it becomes reproduced more and more, and each reproduction removes us more and more from the original.

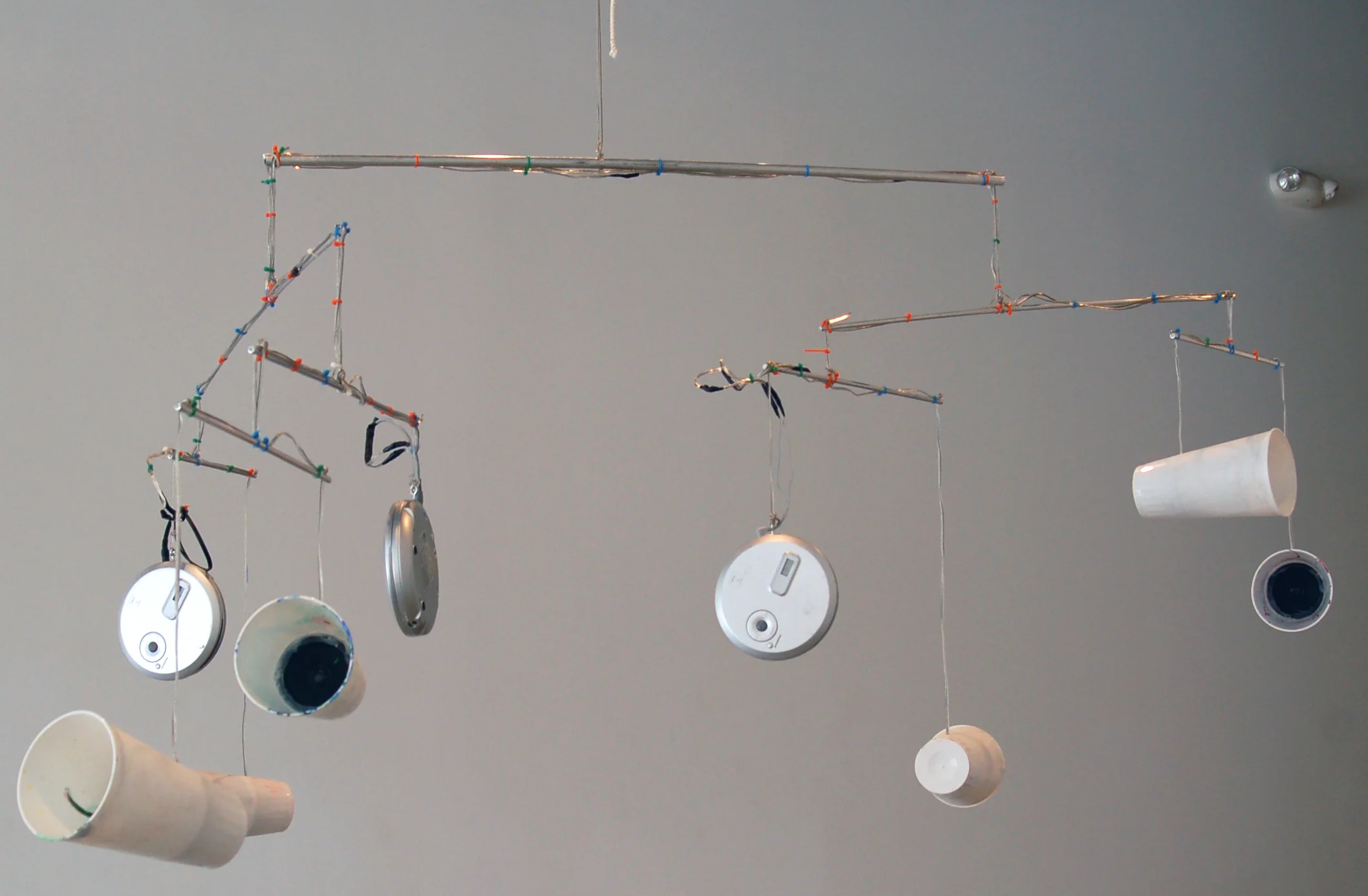

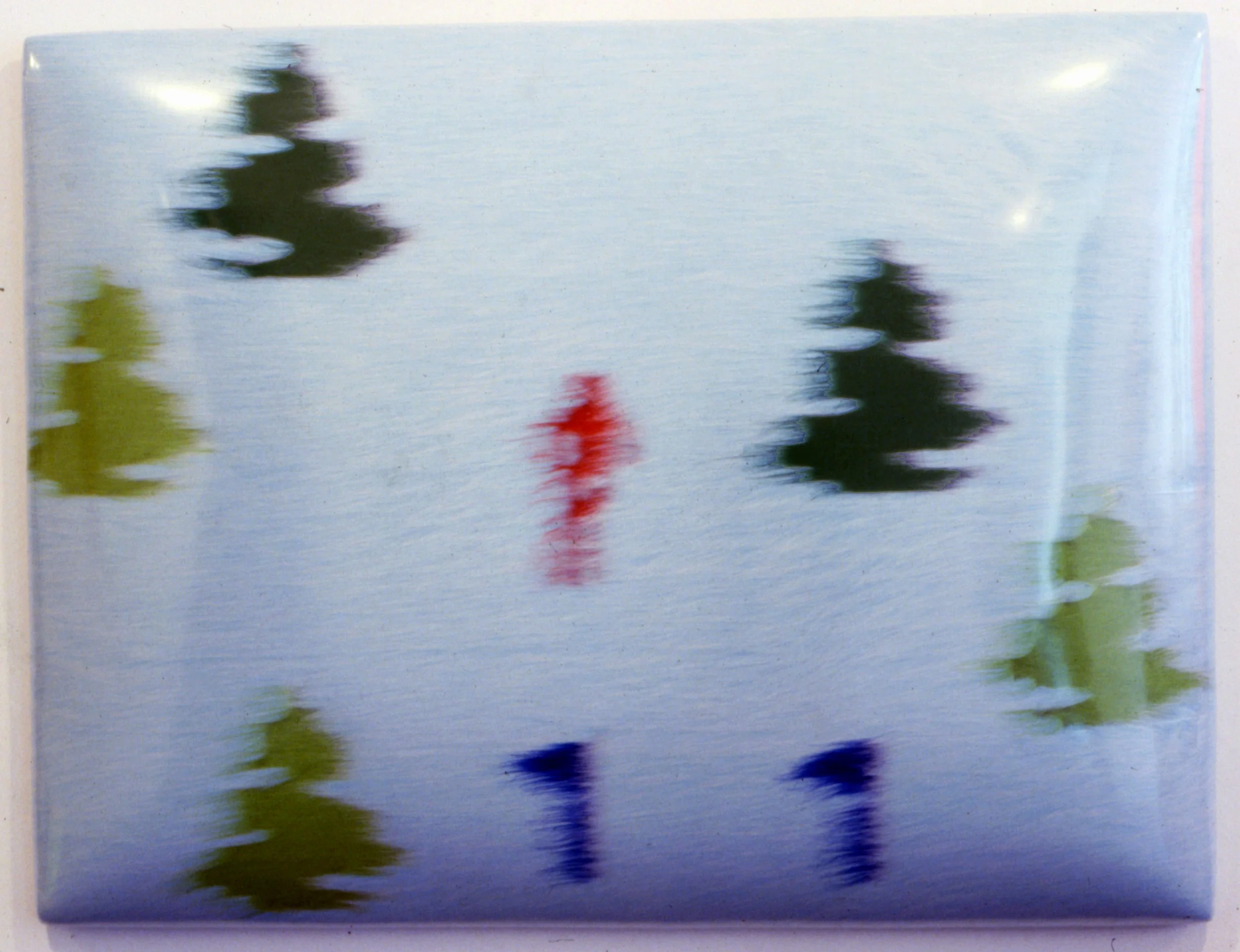

The turntable pieces are essentially viewer-interactive—it is the viewer who must place the record on the turntable and then the tone arms onto the record. Duffy took a giant step towards involving multiple viewers with The Grove (2007), his first museum installation, co-organized by the Luckman Gallery at California State University, Los Angeles and the Arizona State University Art Museum.[4] The Grove is a variable installation, composed of about twenty turntable perched upon folding wooden tables and scattered about the gallery, each accompanied by a bin of records. Each turntable is attached to about twenty miniature speakers (hence about 400 speakers). The speaker cords rise in a bundle from the turntable to the ceiling, like wispy tree trunks, but the speakers then fan out across the gallery, creating a virtual canopy. Visitors were invited to select records from the bins and put them on the turntables and were able to control the speed at which the records were played (33 1/3, 45, and 78 rpm) and the volume. But the catch was that they didn’t know out of which speakers “their” records would play. The entire gallery thus became an aural forest whose sounds were “oddities and anomalies from the 1950s to the 1970s, the peak of vinyl’s popularity. World sounds, pop vocals, religious music, novelty recordings from the forest or the ocean, instrumentals, comedy: There’s nothing too familiar or overbearing, nothing you’d hear on the radio bar the odd Beethoven piece.”[5] Whether one operated a turntable or wandered idly through the gallery, one was surrounded by a mélange of sounds of other people’s choosing.

Duffy’s New Work project for MAM is his second large-scale installation. Like Third Motorcycle, it is autobiographically rooted, but at a remove. He is essentially exploring a family (and by extension, cultural) Golden Age, one in which he was too young to participate directly and which exists for him only as mediated by photographs and other family members’ memories. The centerpiece of the installation is a vintage Toyota Land Cruiser gaudily painted with zebra-stripes. It is a recreation of a car that his father raced in the mid-to-late 1960s, notably in the 1968 Mexican 1000 Rally, an off-road vehicle race that ran down the Baja California peninsula from Ensenada to La Paz.[6] The car was modified by Duffy’s father, Thomas Graham Duffy, then a municipal judge in El Cajon, CA, and a boyhood friend. The car was painted with its distinctive stripes (based on actual zebra patterns, rather than just geometrically striped) by Duffy’s mother and three older sisters in order to make it easily identifiable. But the zebra striping was also an allusion the “Tijuana zebra,” a counterfeit exotic creature popular in the Baja border town since the 1930s. Tourists had liked having their pictures taken (for a fee) with or atop the region’s distinct white burros, but the animals did not show up well in black and white pictures. By painting the burros with stripes, the owners exoticized the animals, causing more people to want to have their pictures taken with them, and allowed them to show up better in snapshots.

Duffy has meticulously modified a Land Cruiser he bought second hand so that it fully resembles the car his father drove. “I felt it was very important that it be created in the same spirit as the original cars. Which meant I should do as much of the work in my garage as possible…. This has given me a feeling for what the race cars were all about. They were built quickly and not always precisely, with functionality and durability being most important. If I’d sent the car out I don’t think I would have learned as much about how they were put together and that would’ve come through in the final piece. I really think that people have a feel for how things are made when they stand in front of it and that’s important to this piece.”[7] In other words, in an effort to retrieve the vehicle from the filter of memory, Duffy felt compelled to recreate it with utmost fidelity. In a broader sense he is recovering the entire Southern California car culture of the 60s from its myth by faithfully engaging in it—all the while, of course, presenting a mediated version of it to his audience.

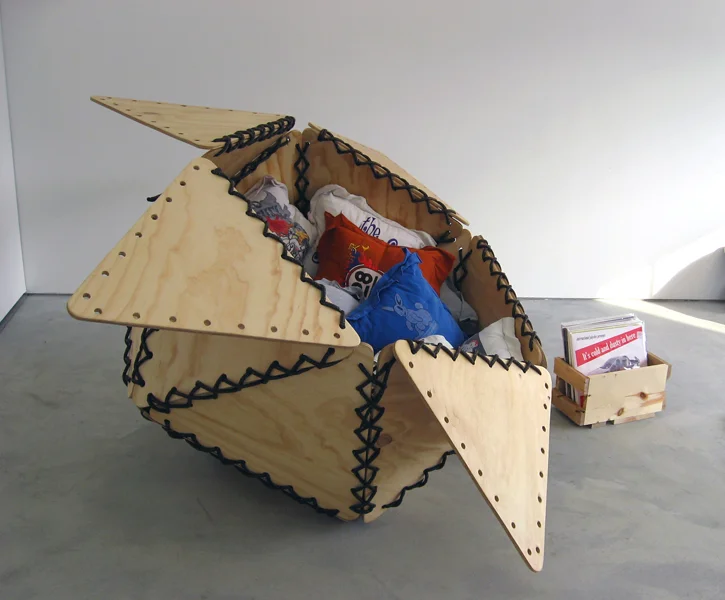

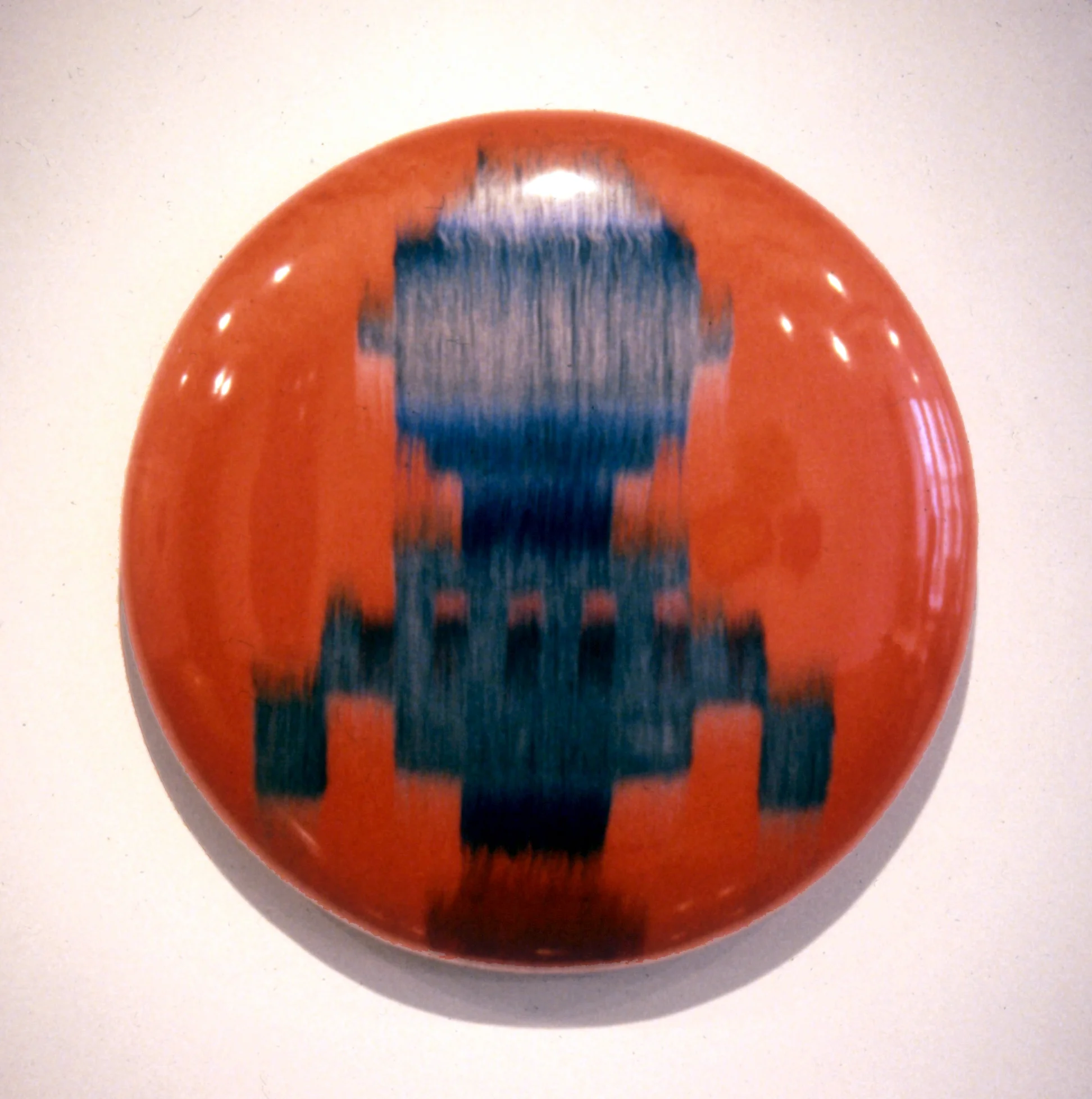

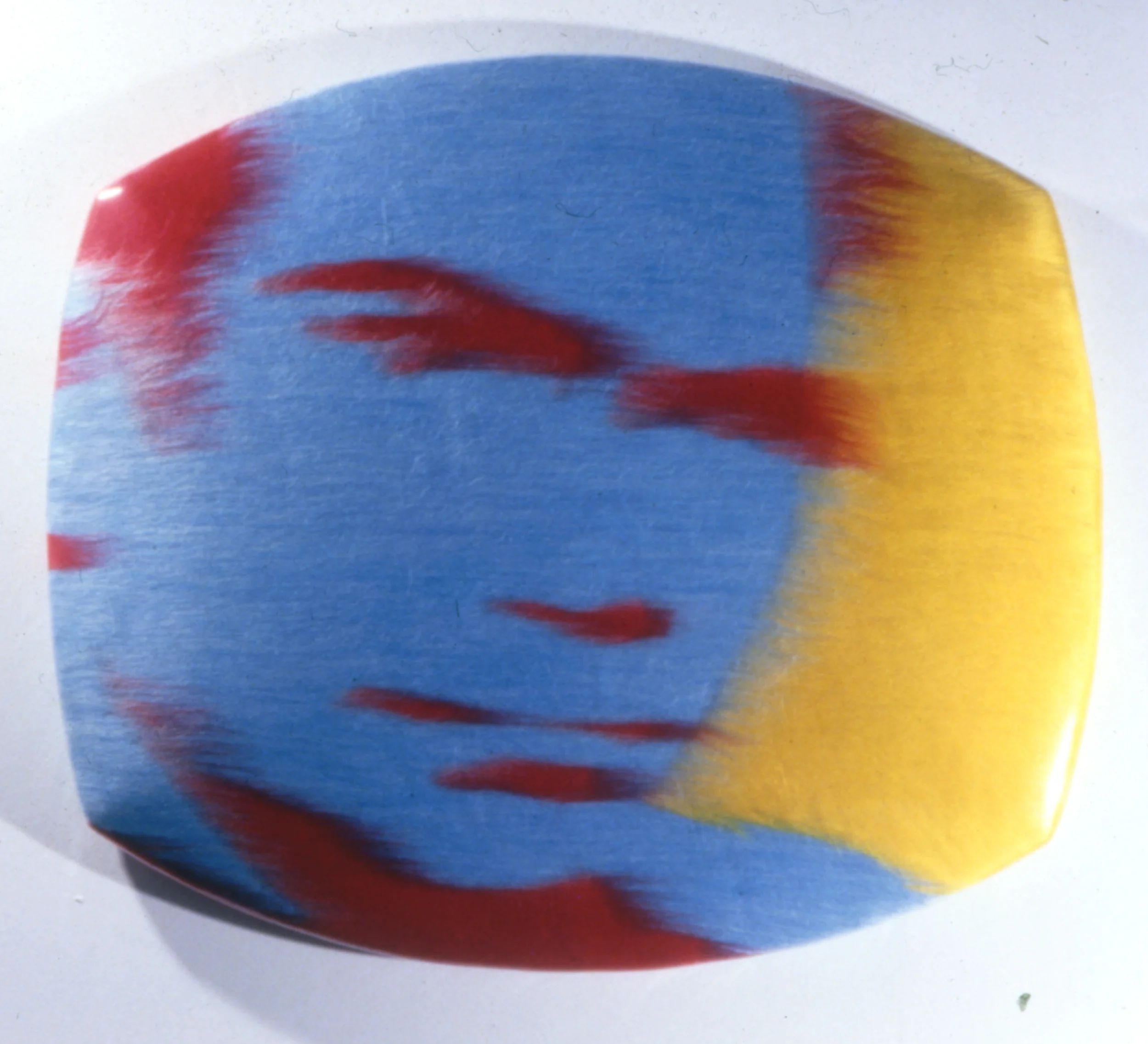

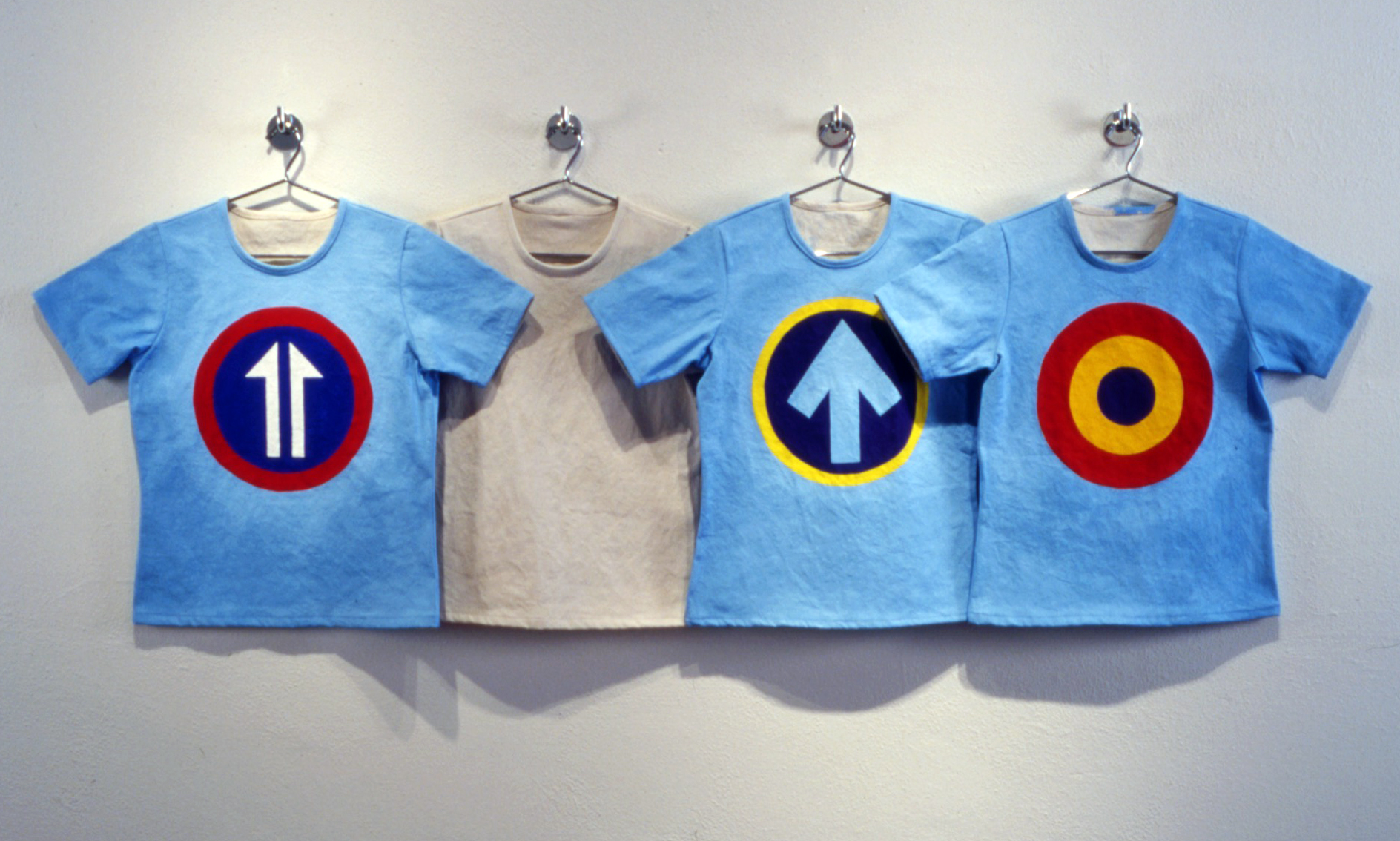

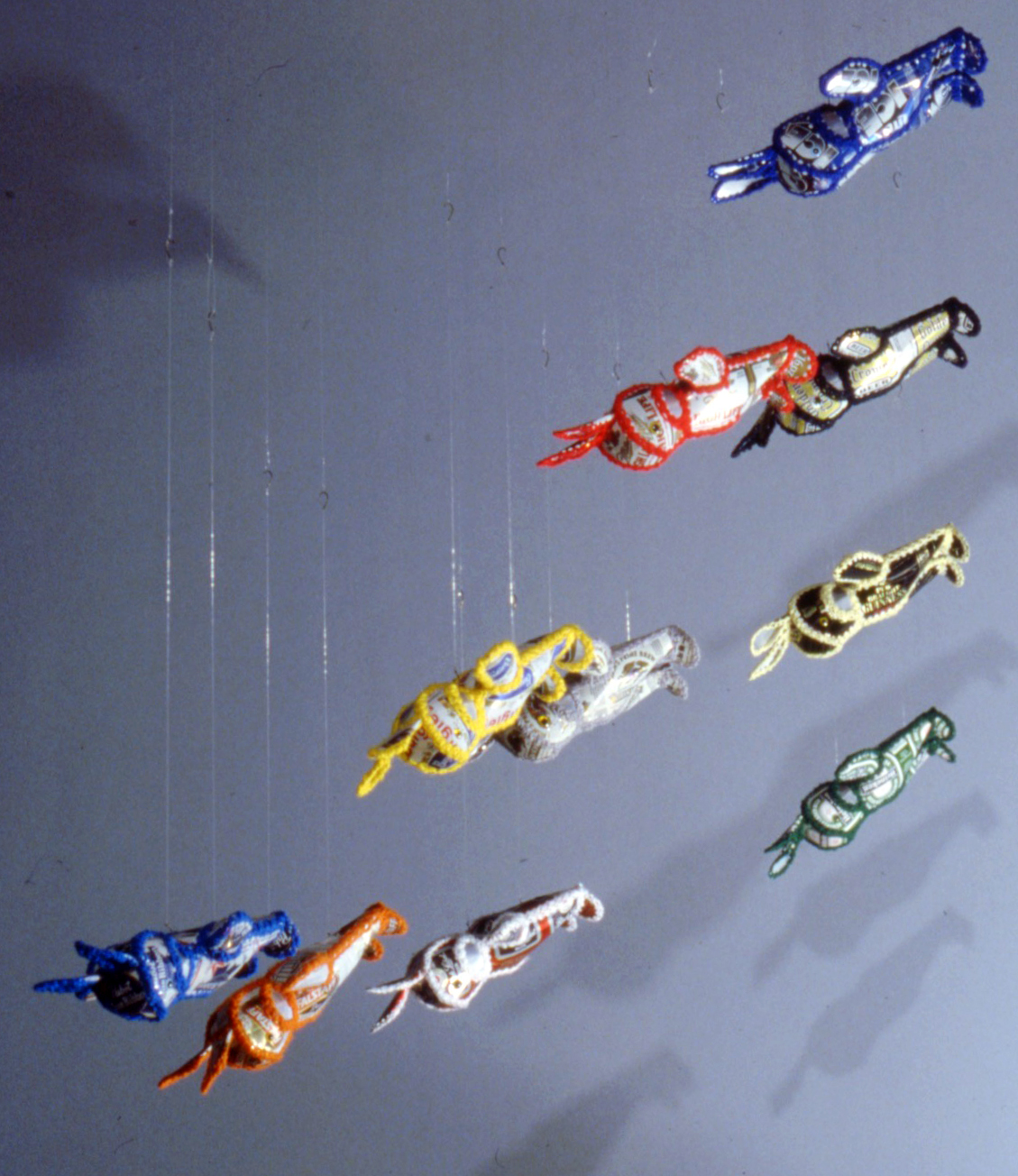

In the installation, the vehicle is accompanied by two other elements: a series of modified “Jerry can” gasoline containers and a pair of paintings made by silk-screening logos and images from car culture onto industrial tarps. The logos come from a box of stickers Duffy had collected in his youth. The Jerry cans are a combination of authentic period cans and modern reproductions, but have been modified so that they act as speakers, playing “covers” of 60s pop tunes piped into them.

An important underlying aspect of the installation is that all three major components, the Toyota, the Jerry cans, and the tarps, are elements of 60s leisure culture that have been recycled from objects that had previous histories. “My dad also served in the Navy at the tail end of World War 2,” writes Duffy, “The entire show has had this underpinning about war and war surplus. The Toyota Land Cruiser was commissioned by the US Army in post-war Japan. The Jerry cans were basically a copy of the German military gas can (hence ‘Jerry can’). The tarps are ubiquitous military surplus. There’s the psychological element of these men diving into the desert attempting to find ‘something’ that they experienced in their late teens.”

In other words, Duffy is attempting to reclaim the experiences of his father, who was in turn attempting to reclaim something from his own youthful Golden Age (if war can ever be considered such). In the process the artist is recycling objects that were themselves recycled from their original function; they have gone from war to leisure to art.

In his MAM installation, Duffy engages in a process of replication that probes both personal history and, on a larger scale, pop culture’s process of consumption, assimilation, and regurgitation in new form. His art is engaged in a cyclical enterprise that underscores (through amplification) the estranged, mediated nature of contemporary culture while it simultaneously engages in a devotional endeavor to reclaim authenticity. Not content with a nostalgic reverie of a lost Golden Age, Duffy seeks to understand it, to “live it” anew, and in the process gives us a new awareness of our own culture and time.

New Work: Sean Duffy is organized by Miami Art Museum and curated by Assistant Director for Programs/Senior Curator Peter Boswell. It is supported by MAM’s Annual Exhibition Fund.

[1] Christopher Knight, “Around the Galleries: One artist enough for this ‘group’”, Los Angeles Times, April 21, 2006, pp. E22-23.

[2] Chris Balaschak, “Sean Duffy,” Frieze, September 2006, p. 202.

[3] Loc.cit.

[4] Sean Duffy: The Grove, co-organized by the Luckman Gallery, California State University, Los Angeles (January 13 – March 3, 2007) and Arizona State University Art Museum, Tempe (June 2 – September 29, 2007). Traveled to Arcadia University Art Gallery, Glenside, PA (November 8 – December 20, 2007).

[5] William Pym. “Picks: Sean Duffy,” Artforum, November 2007

[6] An outgrowth from unofficial, individual timed runs from Ensenada to La Paz by motorcycles and four-wheeled vehicles, the first multi-vehicle Mexican 1000 Rally was run in November 1967.

[7] E-mail correspondence from the artist to the author, May 18, 2008.